Pre-agriculture gender relations seem bad

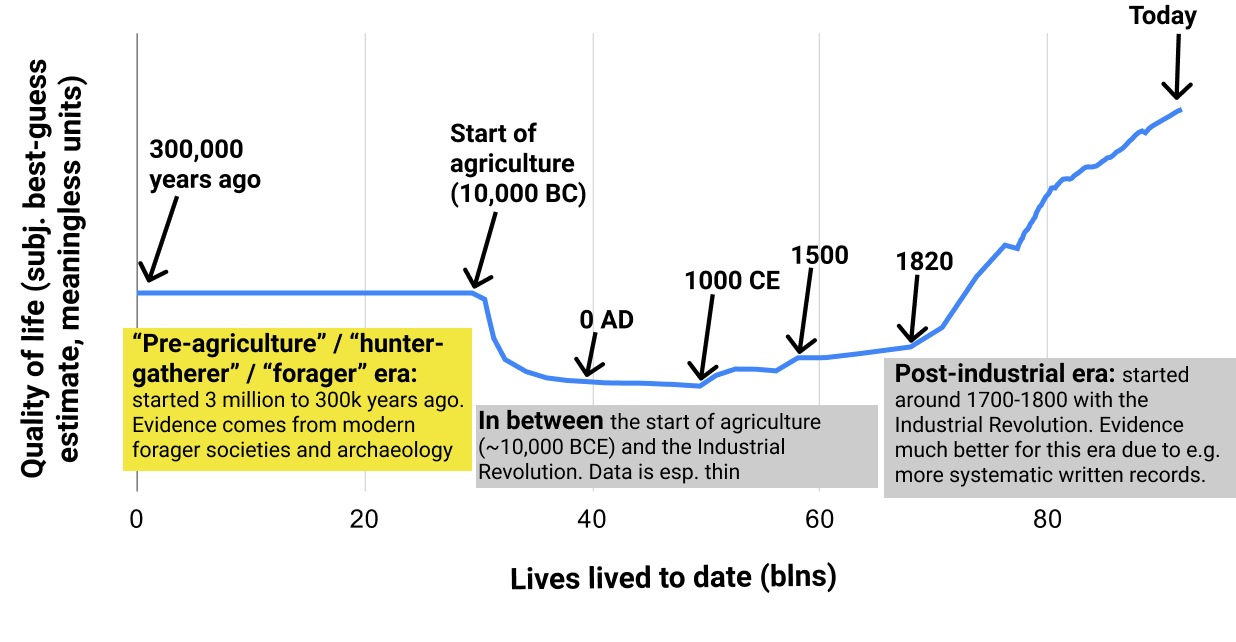

As part of exploring trends in quality of life over the very long run, I've been trying to understand how good life was during the "pre-agriculture" (or "hunter-gatherer"1) period of human history. We have little information about this period, but it lasted hundreds of thousands of years (or more), compared to a mere ~10,000 years post-agriculture.

(For this post, it's not too important exactly what agriculture means. But it roughly refers to being able to domesticate plants and livestock, rather than living only off of existing resources in an area. Agriculture is what first allowed large populations to stay in one area indefinitely, and is generally believed to be crucial to the development of much of what we think of as "civilization."2)

This image illustrates how this post fits into the full "Has Life Gotten Better?" series.

There are arguments floating around implying that the hunter-gatherer/pre-agriculture period was a sort of "paradise" in which humans lived in an egalitarian state of nature - and that agriculture was a pernicious technology that brought on more crowded, complex societies, which humans still haven't really "adapted" to. If that's true, it could mean that "progress" has left us worse off over the long run, even if trends over the last few hundred years have been positive.

A future post will comprehensively examine this "pre-agriculture paradise" idea. For now, I just want to focus on one aspect: gender relations. This has been one of the more complex and confusing aspects to learn about. My current impression is that:

- There's no easy way to determine "what the literature says" or "what the experts think" about pre-agriculture gender in/equality. That is, there's no source that comprehensively surveys the evidence or expert opinion.

- According to the best/most systematic evidence I could find (from observing modern non-agricultural societies), pre-agriculture gender relations seem bad. For example, most societies seem to have no possibility for female leaders, and limited or no female voice in intra-band affairs.

- There are a lot of claims to the contrary floating around, but (IMO) without good evidence. For example, the Wikipedia entry for "hunter-gatherer" gives the strong impression that nonagricultural societies have strong gender equality, as does a Google search for "hunter-gatherer gender relations." But the sources cited seem very thin and often only tangentially related to the claims; furthermore, they:

- Often use reasoning that seems like a huge stretch to me. For example, one paper appears to argue for strong gender equality among particular Neanderthals based entirely on the observation that they seemed not to eat the sorts of foods traditionally gathered by women. (The implication being that since women must have been doing something, they were probably hunting along with the men.)

- Often seem to acknowledge significant inequality, while seemingly trying to explain it away with strange statements like "women know how to deal with physical aggression, unlike their Western counterparts." (Verbatim quote.)

- Seem to get disproportionate attention from very thin evidence, such as an analysis of 27 skeletal remains being featured in the New York Times and a National Geographic article that ranks 2nd in the Google results for "hunter-gatherer gender relations."

Based on the latter points, it seems that there are people trying hard to make the case for gender equality among hunter-gatherers, but not having much to back up this case. One reason for this might be a fear that if people think gender inequality is "ancient" or "natural," they might conclude that it is also "good" and not to be changed. So for the avoidance of doubt: my general perspective is that the "state of nature" is bad compared to today's world. When I say that pre-agricultural societies probably had disappointingly low levels of gender equality, I'm not saying that this inequality is inevitable or "something we should live with" - just the opposite.

Systematic evidence on pre-agriculture gender relations

The best source on pre-agriculture gender relations I've found is Hayden, Deal, Cannon and Casey (1986): "Ecological Determinants of Women's Status Among Hunter/Gatherers." I discuss how I found it, and why I consider it the best source I've found, here.

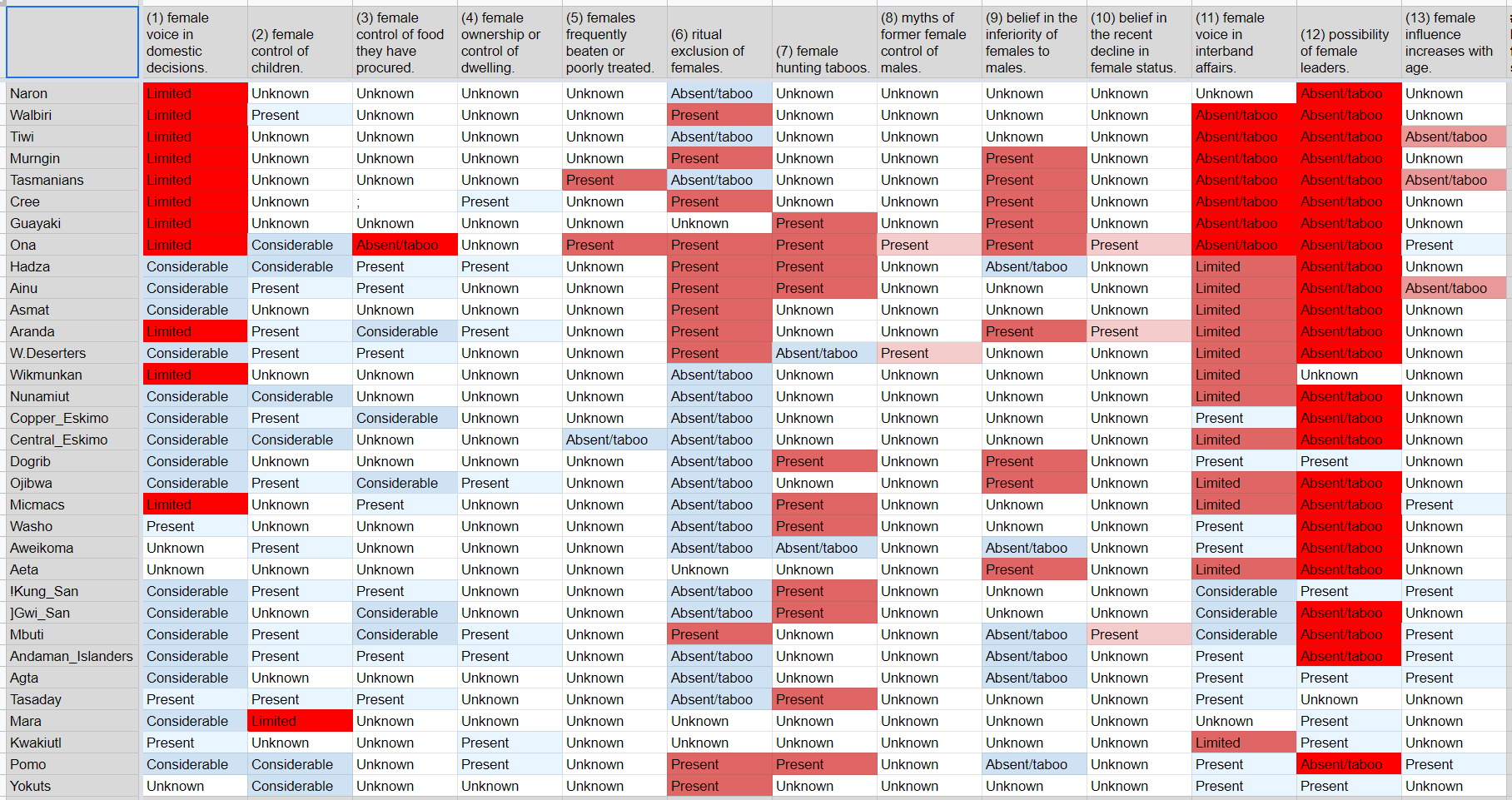

It is a paper collecting ethnographic data: data from anthropologists' observations of the relatively few people who maintain or maintained a "forager"/"hunter-gatherer" (nonagricultural) lifestyle in modern times. It presents a table of 33 different societies, scored on 13 different properties such as whether a given society has "female voice in domestic decisions" and "possibility of female leaders."

Here's the key table from the paper, with some additional color-coding that I've added (spreadsheet here):

I've used red shading for properties that imply male domination, and blue shading for properties that imply egalitarianism (all else equal).3 The red shades are deeper than the blue shades because I think the "nonegalitarian" properties are much more bad than the "egalitarian" properties are good (for example, I think "possibility of female leaders" being "absent/taboo" is extremely bad; I don't think "female voice in domestic decisions" being "Considerable" makes up for it).

From this table, it seems that:

- 25 of 33 societies appear to have no possibility for female leaders.

- 19 of 33 societies appear to have limited or no female voice in intraband affairs.

- Of the 6 societies (<20%) where neither of these apply:

- The Dogrib have "female hunting taboos" and "belief in the inferiority of females to males."

- The !Kung and Tasaday have "female hunting taboos."

- The Yokuts have "ritual exclusion of females."

- The Mara and Agta seem like the best candidates for egalitarian societies. (The Mara have "limited" "female control of children," but it's not clear how to interpret this.)

Overall, I would characterize this general picture as one of bad gender relations: it looks as though most of these societies have rules and/or norms that aggressively and categorically limit women's influence and activities.

I got a similar picture from the chapter on gender relations from The Lifeways of Hunter-Gatherers (more here on why I emphasize this source).

- It states: "even the most egalitarian of foraging societies are not truly egalitarian because men, without the need to bear and breastfeed children, are in a better position than women to give away highly desired food and hence acquire prestige. The potential for status inequalities between men and women in foraging societies (see Chapter 9) is rooted in the division of labor."

- It also argues that many practices sometimes taken as evidence of equality (such as matrilocality) are not.

The (AFAICT poorly cited and unconvincing) case that pre-agriculture gender relations were egalitarian

I think there are a fair number of people and papers floating around that are aiming to give an impression that pre-agriculture gender relations were highly egalitarian.

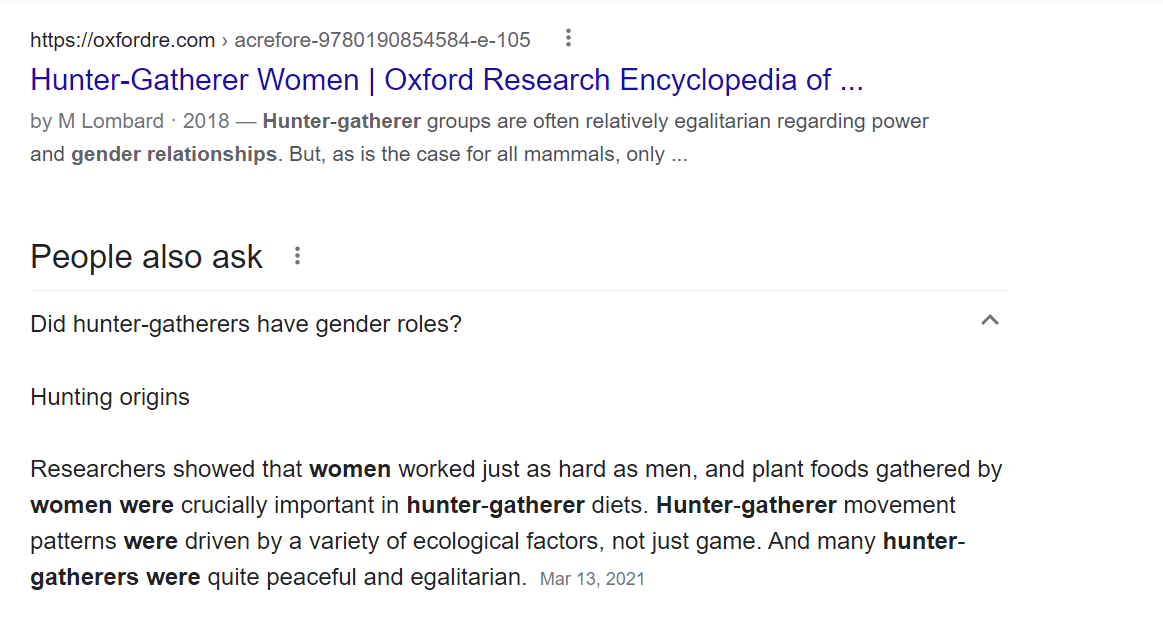

In fact, when I started this investigation, I initially thought that gender equality was the consensus view, because both Google searches and Wikipedia content gave this impression. Not only do both emphasize gender equality among foragers/hunter-gatherers, but neither presents this as a two-sided debate.

Below, I'll go through what I found by following citations from (a) the Wikipedia "hunter-gatherer" page; (b) the front page from searching Google for "hunter-gatherer gender relations." I'm not surprised that Google and Wikipedia are imperfect here, but I found it somewhat remarkable how consistently the "initial impression" given was of strong gender equality, and how consistently this impression was unsupported by sources. I think it gives a good feel for the broader phenomenon of "unsupported claims about gender equality floating around."

Wikipedia's "hunter-gatherer" page

The Wikipedia entry for "hunter-gatherer" (archived version) gives the strong impression that nonagricultural societies have strong gender equality. Key quotes:

Nearly all African hunter-gatherers are egalitarian, with women roughly as influential and powerful as men.[22][23][24] ... In addition to social and economic equality in hunter-gatherer societies, there is often, though not always, relative gender equality as well.[30]

The citations given don't seem to support this statement. Details follow (I look at notes 22, 23, 24, and 30 - all of the notes from the above quote) - you can skip to the next section if you aren't interested in these details, but I found it somewhat striking and worth sharing just how bad the situation seems to be here.

Note 22 refers to a chapter ("Gender relations in hunter-gatherer societies") in this book. I found it to have a combination of:

Very broad claims about gender equality, which I consider less trustworthy than the sort of systematic, specifics-based analysis above. Key quote:

Various anthropologists who have done fieldwork with hunter-gatherers have described gender relations in at least some foraging societies as symmetrical, complementary, nonhierarchical, or egalitarian. Turnbull writes of the Mbuti: “A woman is in no way the social inferior of a man” (1965:271). Draper notes that “the !Kung society may be the least sexist of any we have experienced” (1975:77), and Lee describes the !Kung (now known as Ju/’hoansi) as “fiercely egalitarian” (1979:244). Estioko-Griffin and Griffin report: “Agta women are equal to men” (1981:140). Batek men and women are free to decide their own movements, activities, and relationships, and neither gender holds an economic, religious, or social advantage over the other (K. L. Endicott 1979, 1981, 1992, K. M. Endicott 1979). Gardner reports that Paliyans value individual autonomy and economic self-sufficiency, and “seem to carry egalitarianism, common to so many simple societies, to an extreme” (1972:405).

Of the five societies named, two (Batek, Paliyan) are not included in the table above; two (!Kung, Agta) are among the most egalitarian according to the table above (although the !Kung are listed as having female hunting taboos); and one (Mbuti) is listed as having "ritual exclusion of females" and no "possibility of female leaders." I trust specific claims like the latter more than broader claims like "A woman is in no way the social inferior of a man."

I actually wrote that before noticing, in the next section, that the same author who says "A woman is in no way the social inferior of a man" also observes that "a certain amount of wife-beating is considered good, and the wife is expected to fight back" - of the same society!

Seeming concessions of significant inequality, sometimes accompanied by defenses of this that I find bizarre. Some example quotes from the chapter:

- "Some Australian Aboriginal men use threats of gang-rape to keep women away from their secret ceremonies. Burbank argues that Aborigines accept physical aggression as a 'legitimate form of social action' and limit it through ritual (1994:31, 29). Further, women know how to deal with physical aggression, unlike their Western counterparts (Burbank 1994:19)."

- "For the Mbuti, 'a certain amount of wife-beating is considered good, and the wife is expected to fight back' (Turnbull 1965:287), but too much violence results in intervention by kin or in divorce."

- "Observing that Chipewyan women defer to their husbands in public but not in private, Sharp cautions against assuming this means that men control women: 'If public deference, or the appearance of it, is an expression of power between the genders, it is a most uncertain and imperfect measure of power relations. Polite behavior can be most misleading precisely because of its conspicuousness'"

- "Some foragers place the formalities of decision-making in male hands, but expect women to influence or ratify the decisions"

- "Aché men and women traditionally participated in band-level decisions, though 'some men commanded more respect and held more personal power than any woman.'"

- "Rather than assigning all authority in economic, political, or religious matters to one gender or the other, hunter-gatherers tend to leave decision-making about men’s work and areas of expertise to men, and about women’s work and expertise to women, either as groups or individuals"

Overall, this chapter actively reinforced my impression that gender equality among the relevant societies is disappointingly low on the whole.

Note 24 goes to this paper. (Note 23 also cites it, which is why I'm skipping to Note 24 for now.) My rough summary is:

- Much of the paper discusses a single set of human remains from ~9,000 years ago that the author believes was (a) a 17-19-year-old female who (b) was buried with big-game hunting tools.

- It also states that out of 27 individuals in the data set the authors considered who (a) appear to have been buried with big-game hunting tools (b) have a hypothesized sex, 11 were female and 16 were male.

I think the idea is that these findings undermine the idea that women couldn't be big-game hunters.

I have many objections to this paper being one of three sources cited for the claim "Nearly all African hunter-gatherers are egalitarian, with women roughly as influential and powerful as men."

- None of these results are from Africa (they're from the Americas).

- This is a single paper that seems to be engaging in a lot of guesswork around a small number of remains, and seems to be written with a pretty strong agenda (see the intro). In general, I think it's a bad idea to put much weight on a single data source; I prefer systematic, aggregative analyses like the one I examine above.

- It already seems to be widely acknowledged that the amount of big-game female hunting in these societies is not zero4 (though it is believed to be rare and in some cases taboo), so a small-sample-size case where it was relatively common would not necessarily contradict what's already widely believed.

- Finally, what would it tell us if women participated equally in big-game hunting 9,000 years ago, given that (as the authors of this paper state) there are only "trace levels of participation observed among ethnographic hunter-gatherers and contemporary societies"? As far as I can tell, it's very hard to glean much information about gender relations from 9,000 years ago, and there are any number of different axes other than hunting along which there may have been discrimination. I think it would be quite a leap from "Women participated equally in big-game hunting" to "Gender equality was strong."

Note 23 goes to a New York Times article that is mostly about the above paper. It also cites a case where remains were found of a man and woman buried together near servants; I do not know what point that is making.

Source 30 appears to primarily be drawing from "Women's Status in Egalitarian Society," a chapter from this book.5

I find this chapter extremely unconvincing, and reminiscent of Source 22 above, in that it combines (a) sweeping statements without specifics or citations; (b) scattered statements about individual societies; (c) acknowledgements of what sound to me like disappointingly low levels of gender equality, accompanied by bizarre defenses. (One key quote, which sounds to me like it's basically arguing "Gender relations were good because women had high status due to their role in childbearing," is in a footnote.6)

Google results for "hunter-gatherer gender relations"

Googling "hunter-gatherer gender relations" (archived link) initially gives an impression of strong gender equality. Here's how the search starts off:

However, when I clicked through to the first result, I found that the statement highlighted by Google ("Hunter-gatherer groups are often relatively egalitarian regarding power and gender relationships") appears to be an aside: no citation or evidence is given, and it is not the main topic of the paper. Most of the paper discusses the differing activities of men and women (e.g., big-game hunting vs. other food provision).7

The answer box has no citations, so I can't assess where that's coming from.

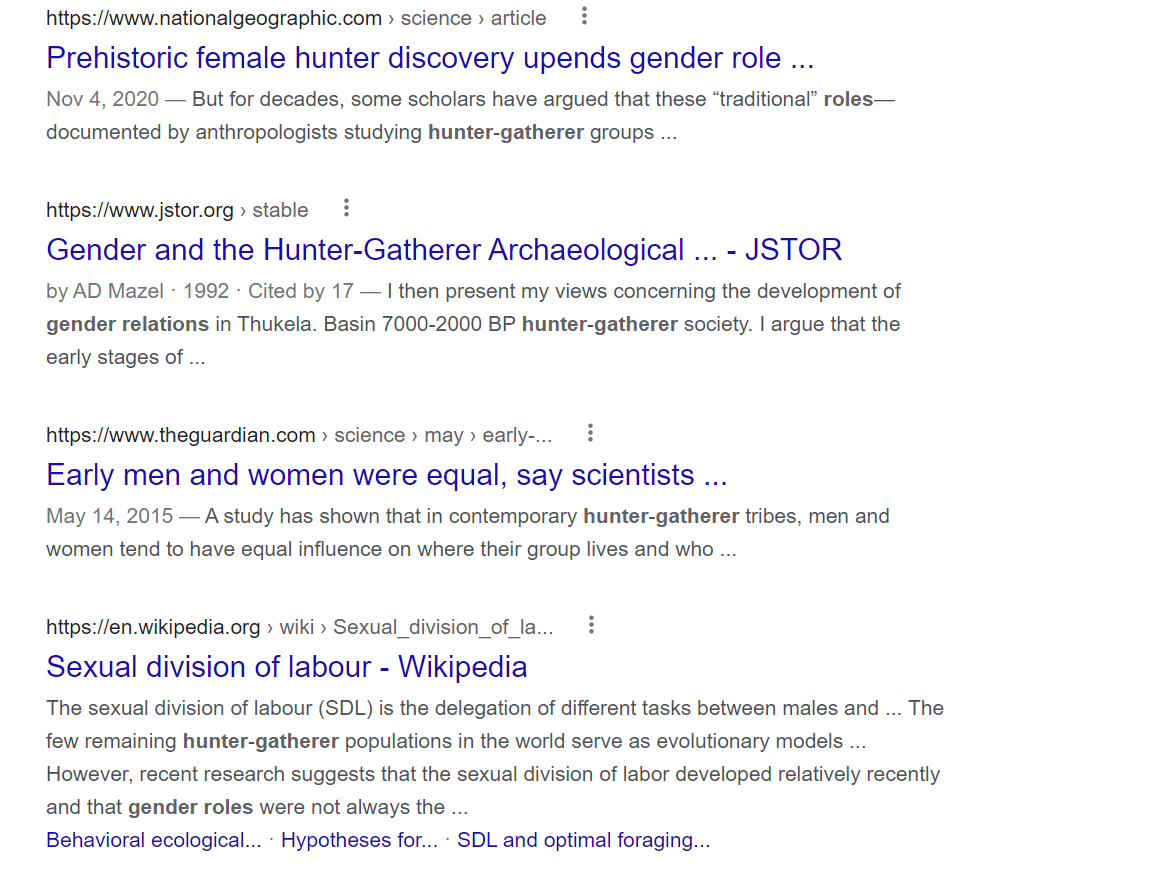

And here's what shows next in the search:

The first of these results (the National Geographic article) is essentially a summary of the same source discussed above that cites evidence of 11 females (compared to 16 males) buried with big-game hunting tools 9,000 years ago.

The next (from jstor.org) is a discussion of "gender relations in the Thukela Basin 7000-2000 BP hunter-gatherer society." The abstract states: "I argue that the early stages of this occupation were characterized by male dominance which then became the site of considerable struggle which resulted in women improving their positions and possibly attaining some form of parity with men."

The next (from theguardian.com) is a Guardian article with the headline: "Early men and women were equal, say scientists." The entire article discusses a single study:

- The study looks at two foraging societies (one of which is the Agta, the most egalitarian society according to the table above).

- It presents a theoretical model according to which one gender dominating decisions about who lives where would result in high levels of within-camp relatedness, and observes that actual patterns of within-camp relatedness are relatively low, so they more closely match a dynamic in which both genders influence decisions (according to the theoretical model).

- I believe this is essentially zero evidence of anything.

The final result is a Wikipedia article that is mostly about the differing roles for men and women among foragers. The part that provides Google's 3rd excerpt is here (screenshotting so you can get the full experience of the citation notes):

Source 8 looks like the closest thing to a citation for the claim that "the sexual division of labor ... developed relatively recently." It goes to this paper, which seems to me to be making a significant leap from thin evidence. The basic situation, as far as I can tell, is:8

- There is no archaeological evidence that the population in question (Neandertals in Eurasia in the Middle Paleolithic) ate small game or vegetables.

- This implies that they exclusively hunted big game.

- It's hypothesized that women participated equally in big-game hunting. The reasoning is that otherwise, they would have had nothing to do, and this seems implausible to the authors. (There is also some discussion of the lack of other things that would've taken work to make, such as complex clothing.)

I do not think that "Neanderthals didn't eat small game or vegetables" is much of an argument that they had egalitarian division of labor by sex.

Bottom line

My current impression is that today's foraging/hunter-gatherer societies have disappointingly low levels of gender equality, and that this is the best evidence we have about what pre-agriculture gender relations were like.

I'm not sure why casual searching and Wikipedia seem to give such a strong impression to the contrary. It seems to me that there is a fair amount of interest in stretching thin evidence to argue that pre-agriculture societies had strong gender equality.

This might be partly be coming from a fear that if people think gender inequality is "ancient" or "natural," they might conclude that it is also "good" and not to be changed. But as I'll elaborate in future pieces, my general perspective is that the "state of nature" is bad compared to today's world, and I think one of our goals as a society should be to fight things - from sexism to disease - that have afflicted us for most of our history. I don't think it helps that cause to give stretched impressions about what that history looks like.

Next in series: Was life better in hunter-gatherer times?

Use "Feedback" if you have comments/suggestions you want me to see, or if you're up for giving some quick feedback about this post (which I greatly appreciate!) Use "Forum" if you want to discuss this post publicly on the Effective Altruism Forum.

Footnotes

-

Or "forager," though I won't be using that term in this post because I already have enough terms for the same thing. "Hunter-gatherer" seems to be the more common term generally, and is the one favored by Wikipedia. ↩

-

E.g., see Wikipedia on the Neolithic Revolution, stating that agriculture "transformed the small and mobile groups of hunter-gatherers that had hitherto dominated human pre-history into sedentary (non-nomadic) societies based in built-up villages and towns ... These developments, sometimes called the Neolithic package, provided the basis for centralized administrations and political structures, hierarchical ideologies, depersonalized systems of knowledge (e.g. writing), densely populated settlements, specialization and division of labour, more trade, the development of non-portable art and architecture, and greater property ownership." The well-known book Guns, Germs and Steel is about this transition. ↩

-

Though properties (2) and (4) could in some cases imply female advantage rather than egalitarianism per se. ↩

-

The table above lists two societies that specifically do not have "female hunting taboos."

The Lifeways of Hunter Gatherers (which I name above as a relatively systematic source) states that there are "quite a few individual cases of women hunters," and that "One case of women hunters who appear to be a striking exception is that of the Philippine Agta [also the only case from the table above with no evidence against egalitarianism]." In context, I believe it is referring to big-game hunting.

This is despite stating the view (which is shared by the paper I'm discussing now) that modern-day foraging societies have very little participation by women in big-game hunting overall (see the section entitled "Why Do Men Hunt (and Women Not So Much)?" from chapter 8). ↩

-

I initially stated that Wikipedia gave no indication of which part of the book it was pointing at, but a reader pointed out that it gave a page number. That page is the page of the index that includes a number of references to gender-relations-related topics. Most come from the chapter I discuss here; there are also a couple of pages referenced of another chapter, which also cites this one, and which I would characterize along similar lines. ↩

-

"It is also necessary to reexamine the idea that these male activities were in the past more prestigious than the creation of new human beings. I am sympathetic to the scepticism with which women may view the argument that their gift of fertility was as highly valued as or more highly valued than anything men did. Women are too commonly told today to be content with the wondrous ability to give birth and with the presumed propensity for 'motherhood' as defined in saccharine terms. They correctly read such exhortations as saying, 'Do not fight for a change in status.' However, the fact that childbearing is associated with women's present oppression does not mean this was the case in earlier social forms. To the extent that hunting and warring (or, more accurately, sporadic raiding, where it existed) were areas of male ritualization, they were just that: areas of male ritualization. To a greater or lesser extent women participated in the rituals, while to a greater or lesser extent they were also involved in ritual elaborations of generative power, either along with men or separately. To presume the greater importance of male than female participants, or casually to accept the statements to this effect of latter-day day male informants, is to miss the basic function of dichotomized sex-symbolism in egalitarian society. Dichotomization made it possible to ritualize the reciprocal roles of females and males that sustained the group. As ranking began to develop, it became a means of asserting male dominance, and with the full-scale development of classes sex ideologies reinforced inequalities that were basic to exploitative structures."

It seems to me as though a double standard is being applied here: the kind of "dichotomization" the author describes sounds like a serious limitation on self-determination and meritocracy (people participating in activities based on abilities and interests rather than gender roles), and no explanation is given for the author's apparent belief that this dichotomization was unproblematic for past societies but reflected oppression for later societies. ↩

-

From the abstract: "Ethnohistorical and nutritional evidence shows that edible plants and small animals, most often gathered by women, represent an abundant and accessible source of “brain foods.” This is in contrast to the “man the hunter” hypothesis where big-game hunting and meat-eating are seen as prime movers in the development of biological and behavioral traits that distinguish humans from other primates." I am not familiar with that form of the "man the hunter" hypothesis; what I've seen elsewhere implies that men dominate big-game hunting and that big game is often associated with prestige, regardless of whatever nutritional value it does or doesn't have. ↩

-

A bit more on how I identified this as the key part of the paper:

- The paper notes that today's foraging societies generally have a distinct sexual division of labor, but argues that it must have developed after the Middle Paleolithic, because (from the abstract) "The rich archaeological record of Middle Paleolithic cultures in Eurasia suggests that earlier hominins pursued more narrowly focused economies, with women’s activities more closely aligned with those of men ... than in recent forager systems."

- As far as I can tell, the key section arguing this point is "Archaeological Evidence for Gendered Division of Labor before Modern Humans in Eurasia." ↩