Did life get better during the pre-industrial era? (Ehhhh)

This is the final piece in the Has Life Gotten Better? series.

For the last 200 years or so, life has been getting better for the average human in the world.

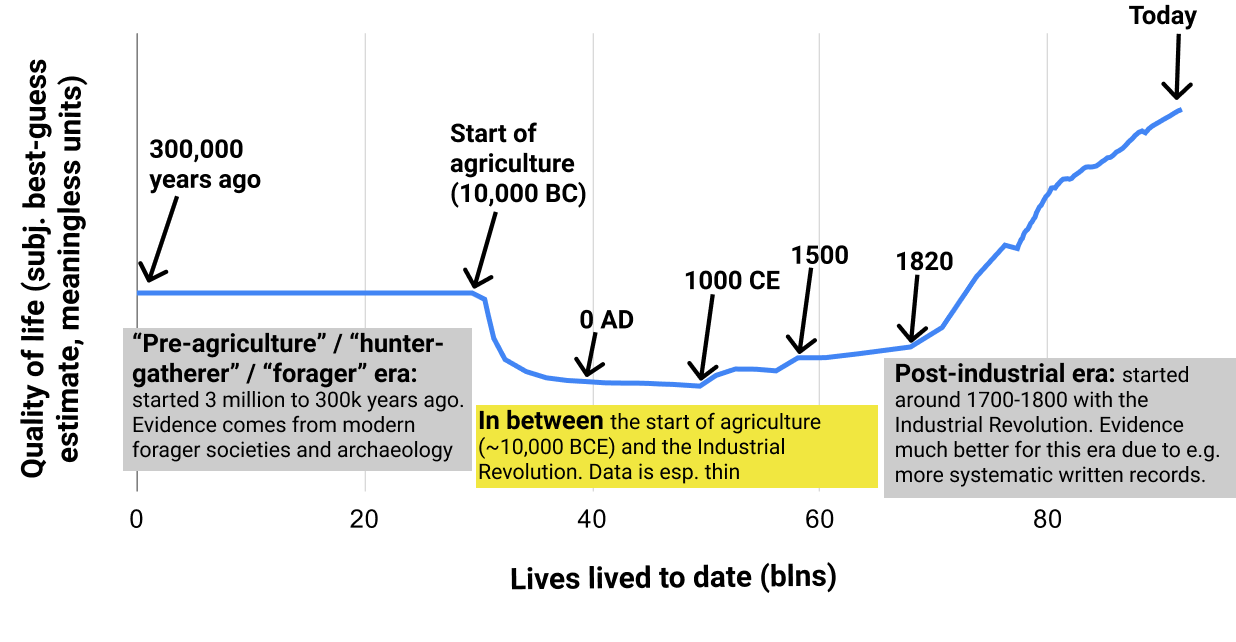

But for the 10,000 years before that, it's not the same story:

- The vast majority of the data we have that could help us understand trends in quality of life only goes back to 1700 or so (at best).

- The little data we do have on the period before that mostly implies that incomes and technological capabilities were increasing slowly (by today's standards), while health, nutrition, human rights, and other drivers of quality of life weren't necessarily on an upward trend at all.

- My guess is that quality of life declined noticeably with the rise of agriculture, starting in about 10,000 BCE - leading to likely increases in the number of people who had to live under intense hierarchy and even slavery.

- Following big increases in quality of life since the Industrial Revolution, I think things are now better than they've ever been (including compared to the pre-agriculture days).

- Beyond these points, I think we know very little.

- It's easy for me to imagine changing my mind pretty quickly and dramatically here.

- If I became more confident in prehistoric life expectancy estimates (which are very low), I might conclude that health was improving significantly (if slowly) throughout just about all of history, perhaps enough to bring my views into line with the simple "There's been a consistent upward trend" view. If I had that sort of view, I might have a stronger default (as I used to) of expecting further advances in wealth, science and technology to keep making life better.

- Another key question is whether pre-agriculture humans were usually like nomadic foragers, or whether sedentary societies were quite common. Right now I'm tentatively presuming that the former is closer to the truth, but if the latter were, that would mean the very distant past is worse than I thought - and would be another point in favor of "Things have been improving this whole time."

- On the other hand, it's easy to imagine new data (such as on happiness) changing my current guess that hunter-gatherer quality of life was worse than today's. In this case, I could end up thinking that scientific and technological advancement have been net negative overall.

- The estimates I've found of the numbers of people enslaved at different points in time seem very rough with a lot of variance. More broadly, my impression is that (prior to the last few hundred years) changes in institutionalized discrimination (such as against women, specific ethnic groups, and LGBTQ+) have been somewhat chaotic. Having better data on these could lead to very different (and more chaotic) pictures of trends in quality of life for the average person.

This post will focus on the period between ~10,000 BCE (when agriculture began) and ~1800 (when the Industrial Revolution led to rapid and clear improvements, discussed previously). This period is the only one I haven't covered so far in the Has Life Gotten Better? series.

I will split this long stretch of time into three periods:

- First, the transition from a world of (probably) mostly nomadic humans (never settling very long in one place) to mostly sedentary humans (living indefinitely in one place), with the rise of agriculture. I will argue that this change, which accompanied the Neolithic Revolution, made quality of life worse for the average person. More

- Second, the long period (thousands of years) between the Neolithic Revolution and the time when we start to have some meaningful records and statistics, which started in Europe around 1300. I'll call this the mystery period. More

- Finally, the period between 1300-1800 - the immediate pre-industrial period. More

Neolithic Revolution

The "Neolithic Revolution" refers to when agriculture started drastically changing lifestyles, and leading to what we tend to think of as "civilization," around 10,000 BCE. Agriculture roughly means living off of domesticated plants and livestock, allowing a large population to live in one area indefinitely rather than needing to move as it runs low on resources.

I think we have some good reasons to think that this transition made life worse for the average person.

As discussed in a supplemental post, the literature on "hunter-gatherer" societies (often studied to figure out what pre-agriculture life was like) tends to emphasize the distinction between two basic types of hunter-gatherer societies (though this is a simplification1):

- One type of society tends to be egalitarian in the sense of having relatively little formal hierarchy. (Though as mentioned in the supplemental post on this, we shouldn't overstate how egalitarian these societies actually are. In particular, they appear to have bad gender relations.) It is often claimed (though I haven't seen it systematically supported) that these societies are usually nomadic - periodically moving in order to get to an area with more resources.

- Another type of society tends to be noticeably more nonegalitarian, with formal status and authority distinctions; prestige displays; and sometime even slavery. This type of society seems to be associated with being sedentary rather than nomadic, meaning people stay in one area indefinitely.

- One rough intuition I've seen to explain the connection is that it's hard to accumulate wealth in a society that periodically relocates (and that lacks cryptocurrency2). I've also seen a number of other explanations.3

Below, I'll give some reasons to believe that:

- The sedentary/nonegalitarian structure probably became a lot more common around the Neolithic Revolution.

- The sedentary/nonegalitarian type of society seems to add some big negatives for the average person's quality of life, without (immediately) compensating positives.

The shift from egalitarian/nomadic to nonegalitarian/sedentary societies

In Hunter-Gatherer and Human Evolution, Richard B. Lee states: "Historically nomadic foragers (HNFs), small in scale, mobile, and egalitarian, reflect most closely the characteristics of ancient foragers."

This is a view that many seem to hold, and is echoed in the main source I've used on forager lifestyles ("Lifeways of Hunter-Gatherers").4 The implication here is that if you go back far enough, all or nearly all people were nomadic/egalitarian.

I have also seen this view disputed, by Better Angels of our Nature as well as one of its key sources (quotes in footnote5). I interpret these sources as guessing something closer to "50% of people in the distant past were nomadic/egalitarian."

I haven't been able to find systematic examinations of what percentage of people were egalitarian/nomadic vs. nonegalitarian/sedentary in the distant past, and I mostly don't expect to, since it seems hard to determine from archaeology. But my best guess (from above) is that it was something in the range of 50-100% of people.

And I think it must have changed either following or sometime before the Neolithic Revolution, which is when agriculture (which allows people to make far more food, far more sustainably, in a single location) started spreading across the world. I'd guess that essentially all agriculture-based societies in premodern times had characteristics more like sedentary/nonegalitarian societies;6 furthermore, agriculture is generally believed to engender much faster population growth (and population estimates accelerated greatly following the Neolithic Revolution).7

For purposes of my oversimplified "Has Life Gotten Better?" chart, I've assumed that 75% of the population was nomadic/egalitarian before 10,000 BCE (this is the midpoint of the 50-100% range I gave), and I've assumed that all net population growth after 10,000 BCE came from agricultural societies.8 That's sufficient to imply a population rapidly going from mostly-egalitarian to mostly-nonegalitarian around that time.

Pros and cons of this transition

As discussed in a supplemental post, it's hard to make definitive statements about nomadic vs. sedentary societies, or agricultural vs. non-agricultural societies, because (from what I've seen) they are not clearly and systematically distinguished in studies (on life expectancy, violence, and other things relevant to quality of life).

So here I am largely going off of impressions from reading the literature, particularly the debates on violence (where people tend to imply that nomadic/egalitarian societies are less violent than sedentary/nonegalitarian ones) and Lifeways (which has a lot of systematic analysis and nuanced discussions throughout, making me generally put a fair amount of weight on its claims). From what I can tell, the claims I'm about to make would be shared by most scholars in the relevant field (though I'm certainly not confident of this and would love to be corrected by any readers who know the field well).

Cons. The main things that jump out at me are:

- Sedentary (including agricultural) societies have formal hierarchy, in the sense of having one leader who has inordinate power over others.9

- Slavery: the only mentions I've seen of slavery among hunter-gatherer societies all refer to nonegalitarian/sedentary societies, particularly the Northwest Coast of North America.10 Slavery seems to have been present in most early agriculture-based states, such as ancient Egypt.

- Violence: it's hard to say for sure, but it seems to me that violent death rates are quite a bit higher among nonegalitarian/sedentary societies than nomadic/egalitarian societies - perhaps ~double - as discussed in this supplemental post.

Pros. I haven't been able to identify any clear ways in which this transition had much immediate benefit for the average person (although it does seem to have led to a lot more people).

In particular:

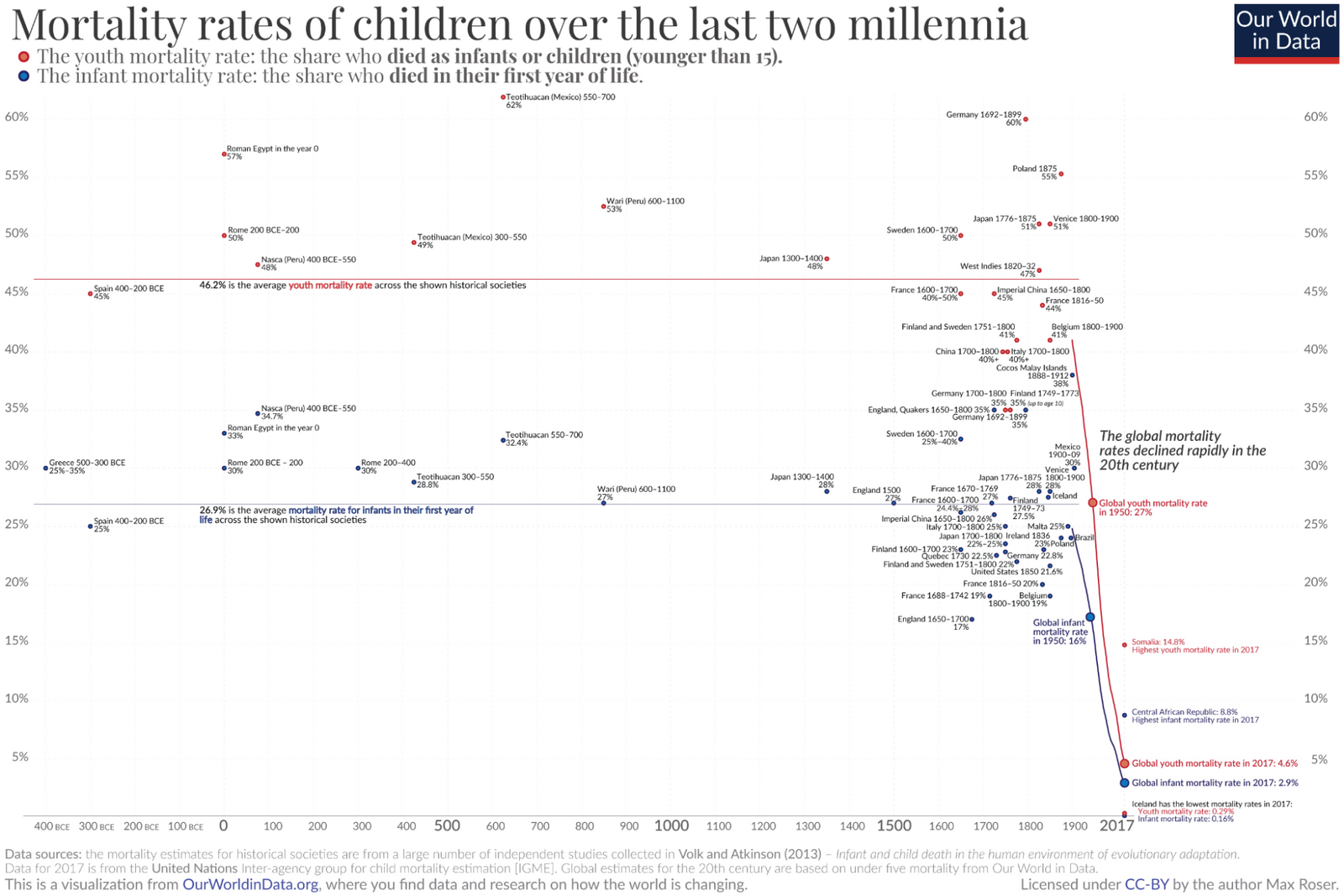

- Infant mortality (deaths before the age of 1) and child mortality (deaths before the age of 15) seem similar for pre-agriculture societies and more recent societies (though rates for both are extremely high by modern standards).

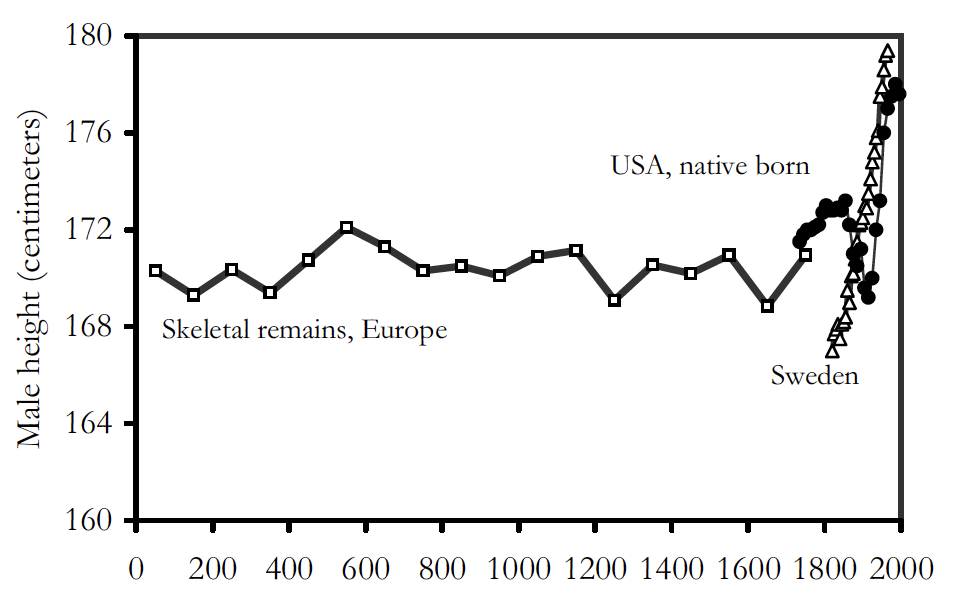

- I previously discussed height as a proxy for hunger, and gave figures implying 1.6-1.68m (5'3" to 5'6") as the pre-agriculture average male height. Compare with later height estimates from European males, of around 1.69m (5'6.5") and 1.64-1.68m (5'5" to 5'6"). A Farewell to Alms argues that the European heights are a bit unrepresentatively high, and that the transition to agriculture brought no benefit on this front.

- This paper claims that today's hunter-gatherer societies have very similar life expectancies to the earliest life expectancies we have on record for 18th century Sweden (around 35 years). It also cites archaeological studies estimating much lower prehistoric life expectancies (closer to 20 years), but argues that these could be unreliable, and that their figures should perhaps be adjusted11 to be closer to the figures from today's hunter-gatherer societies.12

- Additionally, my attempt to find life expectancy estimates from some time in between the Neolithic Revolution and the 18th century largely came up empty; in particular, I found a number of papers arguing that we can say very little about life expectancy in ancient Rome beyond perhaps bounding it between 20-30 years.13

Bottom line: I'd guess that sometime around or before the Neolithic Revolution, we went from most people living in egalitarian/nomadic societies to most people living in nonegalitarian societies with some notable disadvantages and no clear advantages.

Mystery period: between the rise of agriculture and the 1300-1800 period

Nearly all of the data we have seems to be either about extremely early humans (pre-agriculture or at least pre-state) or about the relatively recent past (1300 CE and later).

My rough understanding of why this is:

- To make guesses about the distant past, we can look at currently-existing societies that seem to have "never modernized" in the sense of adopting agriculture or becoming part of large-scale states. We can also look at archaeological remains.

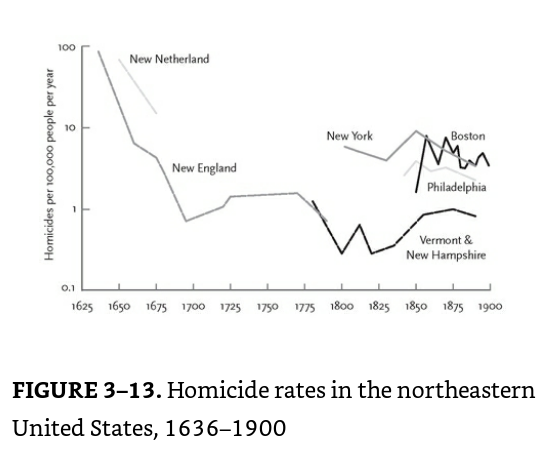

- Starting in 1300 CE, we start to have (in a small number of European countries) systematic written records of things like court cases that make it possible to estimate homicide rates.

- But for the in-between period, we have neither. (It's not clear to me why archaeological remains can't be used for the in-between period, but in practice I have had a lot more trouble finding papers willing to draw conclusions from archaeological remains for this "in-between period," compared to very early periods.)

Some of the few observations I've been able to make:

Infant and child mortality look pretty flat starting around 400 BCE. From Our World in Data:

Height looks flat in Europe starting around the year zero. Again from Our World in Data:

Life expectancy trends are unclear, as noted in the previous section (in particular, see the part about ancient Rome).14

Trends in violent death rates are unclear, and again we lack evidence that there was improvement before the 1300-1800 period (see supplemental post on this).

My qualitative history summary doesn't reveal any clear trends in quality of life - in particular, no clear pattern of rising or falling slavery,15 institutionalized discrimination or gender equality.

"Empowerment" and material incomes seem to have risen sometime between the Neolithic Revolution and ~0 CE, but not risen further for ~1000 years after that. This is what's implied by standard per-capita GDP data,16 and Ian Morris argues this case at length in The Measure of Civilization (key quotes in footnote).17 That is: people had "rising incomes" in some meaningful sense. I've found it hard to pin down exactly in what sense incomes were rising,18 but it appears that a lot of it came down to things like larger buildings; more sophisticated building materials, ornaments and tools; and perhaps richer diets (though it naively looks to me like hunter-gatherer societies have higher meat consumption than most ancient Romans,19 and Morris expresses some skepticism that food consumption was increasing or improving).20

I would guess that higher per-capita incomes did, in fact, have some positive impact on quality of life. But a lot of the point of this post is to ask whether we can distinguish between a "People were getting richer and more powerful, but not better-off" story and a "People were getting better off" story. I think the last few hundred years look clearly like "People were getting better off," but the former story looks quite plausible for the period I'm talking about now.

After 1300 CE

1300 is the earliest year I've seen on the x-axis of a chart, using systematically collected historical data, that seems clearly relevant to quality of life:

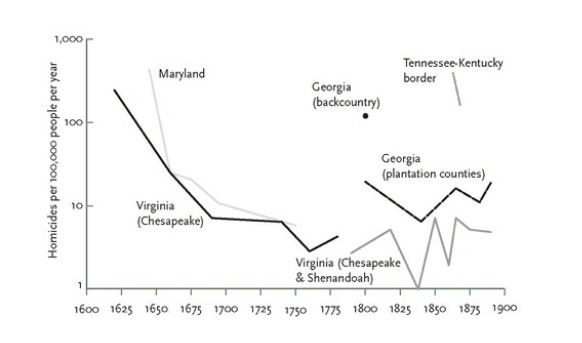

And around 1600, we have similar charts for the US (from Better Angels of our Nature):

I've argued in a supplemental post that the starting homicide rates in these charts aren't necessarily lower than before the Neolithic Revolution. But they seem to fall precipitously as soon as the charts begin. I'm guessing there is some common factor between "recording homicides well enough that a chart like this is possible" and "taking measures to reduce them." And I consider this some sort of good sign about how culture was evolving, even if violent death rates didn't necessarily fall when large-scale atrocities are included.

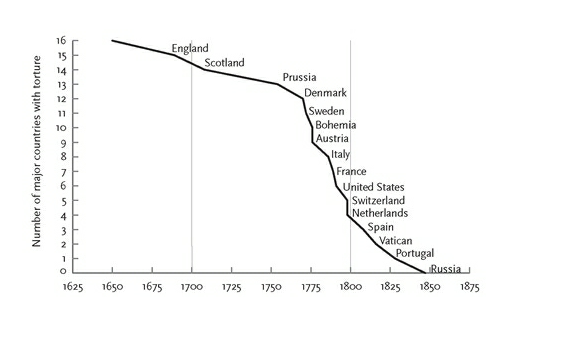

The 17th century also saw a wave of torture bans:

GDP data also show an acceleration in the average person's income rising around this time:21 ~20% from 1000-1300 and another ~20% from 1300-1700, compared to no net growth between 500 BCE and 1000 CE and under 15% growth for all of history before then.

With these points in mind, I'd guess that this is also the period that saw most of whatever improvements in violent death rates, height (as a proxy for hunger) and life expectancy happened before the Industrial Revolution. But that is of course just a guess.

Summary table

| Property | Trend |

| Poverty | Very unclear, and perhaps best proxied by hunger and health, throughout this period. |

| Hunger | Improvement for the average person likely small (if anything); no clear increase in height over this period. |

| Health (physical) | No signs of infant and child mortality improving over this period. Life expectancy likely improved at some point, probably after the year 1300. |

| Violence | Violent death rates look to have ~doubled with the transition to sedentary/nonegalitarian societies, then came back down at some point, possibly after the year 1300. Homicides definitely seem to have been falling at least starting around 1300 in Europe, in the 1600s in the US, though the rise in large-scale atrocities may have partly or fully counterbalanced this. Wave of torture bans started in the 1700s. |

| Mental health | Unknown |

| Substance abuse and addiction | Probably got somewhat worse after the Neolithic Revolution (this is just a guess that alcohol and drugs were uncommon before it); unclear what happened after that. |

| Discrimination | Probably got worse with the transition to nonegalitarian/sedentary societies; started improving, at least in Europe, after 1700. |

| Treatment of children | Unknown |

| Time usage | Unknown |

| Self-assessed well-being | Unknown |

| Education and literacy | Improved at least since the 1500s. |

| Friendship and community | Unknown |

| Freedom | Probably got worse with the rise of agriculture and the accompanying transition to nonegalitarian/sedentary societies; otherwise mostly unclear. |

| Romantic relationship quality | Unknown |

| Job satisfaction | Unknown |

| Meaning and fulfillment | Unknown |

Next in series: Rowing, Steering, Anchoring, Equity, Mutiny

Footnotes

-

Note that in the literature on this topic, the most common distinction is between "simple" and "complex" economies, but I've avoided these terms due to the reservations expressed about them in The Lifeways of Hunter Gatherers, Chapter 9. The book prefers "egalitarian vs. nonegalitarian," which I think does a good job capturing part of what makes this distinction important; I've also emphasized "nomadic" vs. "sedentary" because it's a particularly objective distinction that I've seen emphasized elsewhere. ↩

-

Fine, any currency. ↩

-

From The Lifeways of Hunter Gatherers: "Rather than attributing nonegalitarian foragers simply to “resource abundance,” as many have done in the past, we will see that sedentism, the resource base, geographic circumscription, storage, population pressure, group formation, and enculturative processes all play a role. Therefore, this chapter calls on previous discussions of foraging, mobility, land tenure, exchange, demography, social organization, and marriage." Chapter 9 discusses different theories extensively. ↩

-

"On the strength of archaeological data, it is reasonable to assume that nonegalitarian society developmentally followed egalitarian society. On the northwest coast, for example, slavery appears about 1500 BC, warfare by AD 1000, and nonegalitarian societies by at least AD 200 ... Egalitarian behaviors and an egalitarian ethos were adaptive for quite a long time in human history before the selective balance tipped in favor of nonegalitarian behaviors and a nonegalitarian ethos." ↩

-

From Better Angels of our Nature, Chapter 2: "The nonstate peoples we are most familiar with are the hunters and gatherers living in small bands ... But these people have survived as hunter-gatherers only because they inhabit remote parts of the globe that no one else wants. As such they are not a representative sample of our anarchic ancestors, who may have enjoyed flusher environments. Until recently other foragers parked themselves in valleys and rivers that were teeming with fish and game and that supported a more affluent, complex, and sedentary lifestyle. The Indians of the Pacific Northwest, known for their totem poles and potlatches, are a familiar example."

Bowles 2009, one of the main sources of violence data, seems to take a similar view: "Because hunter-gatherer populations occupying resource-rich areas in the Late Pleistocene [starting over 100,000 years ago] and early Holocene were probably sedentary (at least seasonally), I have included wars involving settled as well as purely mobile populations."

Neither of these sources discusses how many prehistoric people lived in the "flusher" environments as opposed to less "flush" ones; moreover, it's not clear that "flushness" is the main driver of whether societies are egalitarian or nonegalitarian (see Lifeways Chapter 9). ↩

-

Reasons for this:

- In nearly every discussion I've seen of egalitarian/nomadic vs. nonegalitarian/sedentary societies, scholars seem to equate agriculture with the latter.

- Premodern agricultural societies seem to have had most of the properties that Chapter 9 of Lifeways thinks are predictive of nonegalitarian/hierarchical relations.

- I believe nearly all very early state societies had slavery, and (by definition) all had formal hierarchy, which are two of the three main disadvantages I list below for sedentary/nonegalitarian societies. ↩

-

E.g., see the HYDE data set, which starts in 10,000 BCE (the time of the Neolithic Revolution, hundreds of thousands of years after the start of Homo Sapiens) with a population of ~4 million, but reaches ~10 million by 7,000 BCE. ↩

-

In reality, there was probably some population growth from nonagricultural societies, but also probably net conversion of nonagricultural to agricultural societies. So this seems like it will if anything underestimate the speed with which the population became dominated by agricultural societies - and it still leads to that domination happening pretty fast. ↩

-

Here I'm largely reading between the lines on this quote from Lifeways: "Group leaders are common in egalitarian societies – Shoshone 'rabbit bosses' for example – but they are temporary and have their position only because they have demonstrated skill at a particular task. Their leadership does not carry over into other realms of life, nor is it permanent. The process of group formation, however, suggests how the process of leader creation might result in inequality." ↩

-

Lifeways: "We can elucidate these propositions by examining cultural variability along the Northwest Coast of North America, where foragers lived in large, sedentary villages; owned slaves; participated in warfare for booty, food stores, slaves, and land; and where, in some societies, individuals, kinship units, and villages were ranked." It then discusses the Northwest Coast at length as its central example of nonegalitarian foraging societies. ↩

-

"Estimated mortality rates then increase dramatically for prehistoric populations, so that by age 45 they are over seven times greater than those for traditional foragers, even worse than the ratio of captive chimpanzees to foragers. Because these prehistoric populations cannot be very different genetically from the populations surveyed here, there must be systematic biases in the samples and/or in the estimation procedures at older ages where presumably endogenous senescence should dominate as primary cause of death. While excessive warfare could explain the shape of one or more of these typical prehistoric forager mortality profiles, it is improbable that these profiles represent the long-term prehistoric forager mortality profile. Such rapid mortality increase late in life would have severe consequences for our human life history evolution, particularly for senescence in humans. It may be possible to use the data from modern foragers to adjust those estimates for prehistoric foragers." ↩

-

It also claims that life expectancy likely rose after agriculture, but the papers it cites as support for this claim seem to only be about well-pre-agriculture life expectancy. Key quote: "It is usually reported that Paleolithic humans had life expectancies of 15–20 years and that this brief life span persisted over thousands of generations (Cutler 1975; Weiss 1981) until early agriculture less than 10,000 years ago caused appreciable increases to about 25 years. Several prehistoric life tables support this trend, such as those for the Libben site in Ohio (Lovejoy et al. 1977), Indian Knoll in Kentucky (Herrmann and Konigsberg 2002), and Carlston Annis in Kentucky (Mensforth 1990)." I reviewed the cited studies, and the closest thing I found to support was in Lovejoy et al. 1977: "Recent work has demonstrated a marked decrease of adult mortality in cohorts subjected to elevated disease stress in early years (23). This is most probably a direct result of intensified selection for "immunological competence." Those with less adequate genomes are removed from the cohort in early childhood, and the more hardy survivors consequently display depressed mortality. This provides a possible solution to the skeletal-ethnographic sampling discrepancy. Modern "anthropological" populations are virtually all contact societies and remain under the selective influence of a battery of novel pathogens." I wasn't able to locate the citation (23). ↩

-

See Scheidel 2001, Scheidel 2010, and the start of Chapter 2 in this book, which I found to be a pretty interesting read. ↩

-

It does seem like there's a good argument that life expectancy rose sometime in between the Neolithic Revolution and 1810, since life expectancy as of 1810 averaged around 29 worldwide, whereas there are estimates of prehistoric life expectancy that are closer to 20 (but these are disputed, as noted at the link, and it's not out of the question that life expectancy could have been flat over this whole period). If improvement did happen prior to 1810, though, it could've been in the 1300-1800 period discussed below. ↩

-

Also see Luke Muehlhauser on this point. ↩

-

E.g., from the Maddison Project. ↩

-

"Quantitative studies of consumption—including everything from animal bones in settlements to numbers of shipwrecks, levels of lead and tin pollution generated by industrial activity, the scale of deforestation, frequencies of public inscriptions on stone, numbers of coins in circulation, and quantities of archaeological finds along the German frontier—also point the same way: per capita energy capture in the Mediterranean world increased strongly during the first millennium BCE, peaked somewhere between 100 BCE and 200 CE, then fell again in the mid-first millennium CE. Figure 3.5 illustrates the tight fit between the rise and fall of shipwrecks (normally taken as a proxy for the scale of maritime trade) and levels of lead pollution in the well-dated deposits at Penidho Velho in Spain.

"Each category of material has its own difficulties, but no single argument can explain away the striking increase in evidence for nonfood consumption across the first millennium BCE and the peak in the first two centuries CE. The shipwreck data and the vast garbage dumps of transport pottery surrounding the city of Rome (a single one of which, at Monte Testaccio, contains the remains of 25 million pots, used to ship 200 million gallons of olive oil) also attest to the use of nonfood energy to increase food supply and the extraordinary level of consumption of “expensive” food calories. Some scholars also identify an increase in stature in the first to second century CE, although others are more pessimistic, suggesting that adult male Romans in early imperial Italy were typically under 165 cm tall, which would make them shorter than Iron Age or medieval Italians."

"As in Greece, the housing evidence may be the most informative, and Robert Stephan and Geof Kron are now collecting and analyzing this material. Data from Egypt and Italy already suggest that by the first centuries CE typical Roman houses were even bigger than classical Greek houses had been, and that sophisticated (by premodern standards) plumbing, drainage, roofs, and foundations spread far down the social ladder. The explosion of material goods on Roman sites is even more striking. Mass production of wheel-made, well-fired pottery, amphoras for wine and olive oil, and base-metal ornaments and tools reached unprecedented levels in the first few centuries CE. Similarly, distribution maps show that by 200 CE trade networks were more extensive and denser than they would be again until at least the seventeenth century. The scale of trade with India, far outside the empire’s formal boundaries, is particularly impressive."

"Until specialists in late Roman archaeology quantify the evidence more precisely, it will be difficult to make accurate estimates, but between 200 and 700 the general picture is of large houses of stone and brick being replaced by smaller structures of wood and clay; paved streets being replaced by mud paths; sewers and aqueducts stopping working; life expectancy, stature, and population size falling, and the surviving people moving from cities to villages; long-distance trade declining; plain, handmade pottery replacing slipped, wheel-made wares; wood and bone tools being used more often, and metal ones less; factories going out of business and village craftsmen or household producers taking their places." ↩

-

Most studies of real incomes look for records on how much people were paid, and compare it to the price of some standardized set of goods that includes different sorts of food, soap, linen, candles, lamp oil and fuel. For example, Scheidel and Friesen 2009 - which appears to be the main source of wage data for the year 1 AD - references Scheidel 2009, which has its price comparison points on page 4. ↩

-

See Scheidel 2009 page 4 for meat consumption for the "respectability basket," which is considered high-end for ancient Rome, as discussed in Scheidel and Friesen 2009. See Table 3.6 of Lifeways for foraging society meat consumption. ↩

-

"Through most of history per capita nonfood energy capture has tended to rise, but people have had few ways to convert nonfood calories into food. As a result, the difficulty of increasing food calories has been the major brake on both population size and rising living standards." ↩

-

I'm using the Maddison Project-based series from Modeling the Human Trajectory. ↩